Remembering Bruce McLaren, 50 years on

“To do something well is so worthwhile that to die trying to do it better cannot be foolhardy.” It’s not Bruce McLaren’s most famous line, rather the line that came moments before as he tried desperately to comprehend his teammate Timmy Mayer’s untimely loss amidst motorsport’s lethal, pre-safety-conscious era.

Bruce passed away 50 years ago, on 2 June 1970, aged just 32. Anecdotes from teammates suggest his racing career was winding down at the time. In the cockpit, at least. His early years saw him obsessed with engineering and despite an innate knack for driving a car quickly and skilfully, his love of bolting machinery together and honing it to its nth degree never left.

His death came not amid the drama of a motor race, but in a quiet testing session at Goodwood as he attempted to perfect the handling characteristics of teammate Denny Hulme’s McLaren M8D Can-Am car. His own attempt to deal with Timmy’s death surely brought solace to the friends and family he left behind on the day of his own.

Born in New Zealand, Bruce arrived in top-level motorsport via a fairly pioneering route, as the winner of his nation’s very first ‘Driver to Europe’ scheme which aimed to propel the most promising Kiwi talents onto the world stage. While it landed him a seat with British team Cooper, it was no golden ticket to success. Rather than just hop into a car fettled and ready to go, Bruce was an active part of its improvement and development.

Which didn’t bother him one iota. Before his big break he was pursuing a career as an automotive engineer, a passion that grew at home fettling an Austin Seven which now sits proudly in the McLaren Technology Centre entrance. And on his first day in Cooper’s workshop, his new car sat before him in pieces. Bruce had to assemble it before he could race it.

Bruce exhibited an almost voracious appetite for pressure, his most memorable results coming with his back against the wall

It wasn’t long before the paddock knew the name ‘McLaren’, though. He truly shook the establishment with a startling class win on his debut at the Nürburgring in 1958, having pounded a regular saloon around the Nordschleife for practice.

He beat Formula One drivers in a Formula Two car, embarrassing much bigger names - rather like another of motor racing’s icons (and lost heroes) did decades later in a Mercedes 190E.

Bruce’s driving had a tenacity to it, and he exhibited an almost voracious appetite for pressure, his most memorable results coming with his back against the wall. Relegation down the grid by mechanical issue or the petty decree of the stewards was the kick up the arse that led to numerous podiums.

His taste for victory against adversity seemed rooted in his medical struggles as a child; fears ‘he may never walk again’ quickly gave way to a glittering racing career in some of the most physically tough cars to drive.

He was slight, at five foot five, with one leg shorter than the other. But so long as the pedal box was adjusted to suit, it never once got in his way.

He was a talented F1 driver with a broadly unexceptional results tally. His headline wins are his very first in 1959 – in the United States, where he became the youngest Grand Prix winner ever aged 22 – and in Belgium nine years later, where he gave the McLaren team its first ever win at Spa.

“By winning with one’s own car, both other drivers and other cars have been beaten,” Bruce said. Patty, the wife he adored, was on hand to celebrate a truly hard-won victory.

Because despite F1 success, Bruce didn’t indulge in the glamorous trappings of some of his competitors. He had a firm belief a good night’s sleep was the key to success in motorsport, which wasn’t a mantra adopted by some of his more playboy peers.

A dinner party round at Bruce’s house would end up with a dining table full of technical drawings rather than empty bottles. His main indulgence was road cars, ones which by his own admission he often ruined with steering or suspension more suitable for a trackday than long-distance comfort between races. Always engineering…

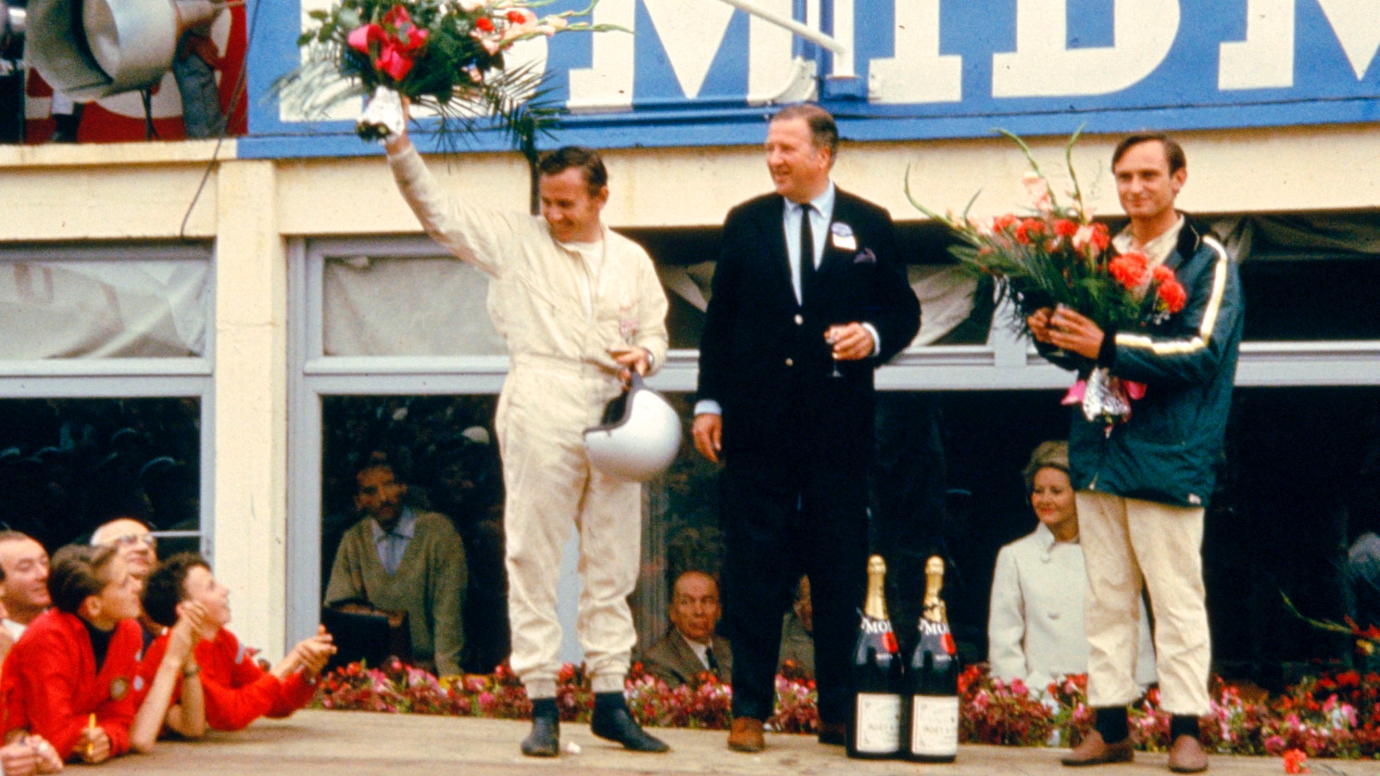

Bruce’s best known victory came at the 1966 Le Mans 24 Hours, where he and a fellow Kiwi, Chris Amon, gave the Ford GT40 the first of its four iconic wins. It came with controversy, McLaren and Amon winning by a technicality when team orders for them to slow down to allow a Ford dead heat went awry.

But Bruce played such a pivotal (and rarely celebrated) part in the GT40’s development – he was key in making it so supremely drivable above 320km/h – he’d perhaps earned that victory more than anyone.

It was his unstoppable enthusiasm as both a driver and an engineer that set him apart, and one of the GT40’s development team – the wonderfully named Chuck Mountain – recalled a driver who didn’t use testing to merely complain about niggles; he had boundless ideas on how to right them.

“Bruce could perceive the problem, define it, and have half a dozen solutions by the time he pulled back into the pits. He’d pick up the most uncanny things – things that were just so remote that you wouldn’t think a guy had the ability to feel or recognise them, but you would check into what he said and make a change and sure in Hell he was right!”

McLaren and Amon are bit parts in the Le Mans ‘66 film, despite winning the blooming thing. But that’s Bruce in a nutshell. He raced with Moss, Clark and Stewart and – on his day – he was as quick as them. Yet his place in the motorsport hall of fame isn’t as front and centre, and while there remains a whole racing team and supercar maker bearing his name, I’d be staggered if 720S buyers can produce his name as quickly as a 488 owner can say ‘Enzo’. Nor tell you the company’s roots are about as far away from Woking as regular civilisation gets.

Sneaky little Kiwis are engraved within every new McLaren road car, but usually on components their drivers will never see, though a recent run of heritage-liveried Elvas is a more welcome nod to Bruce’s era. In fact, the name ‘Elva’ is a very direct reference to sportscars Bruce worked on in the early 1960s.

His lack of blockbuster success in F1 was countered by a hugely successful period in the Canadian-American Challenge Cup – aka Can-Am – where McLaren orange cars won just about every race in the late Sixties, Bruce picking up two championships. This was reflected by fame in the US that dwarfed his status in Europe.

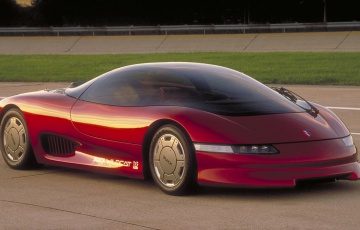

The company’s Can-Am entrants were the basis of McLaren’s first ever road car, too. Bruce used a red M6GT prototype daily and had a list of flaws – difficult ingress and egress, nowhere to store a spare wheel – that he’d fix with a second attempt. A car that sadly never had the chance to come to fruition. Colleagues who drove the M6 report it being surprisingly comfy and relaxing to drive once you’d negotiated its trick entry procedure, something reflected by all of McLaren Automotive’s modern-day line-up.

Bruce’s dream of developing his own cars sowed the seeds for the McLaren racing team and road car arm we have today, but it’s also what led to his untimely loss, as he put in the hard yards meticulously perfecting the M8D that fateful day in 1970. He was tuning the rear spoiler to combat Can-Am’s ban on towering wings when the car’s rear lifted, sending it beyond even his masterful control. It hit a marshal’s post that was overdue demolition and Bruce died instantly.

“Too often someone pays the penalty for being in the wrong place at the wrong time when a situation or set of circumstances is such that no human being can control them,” he’d written in his Autosport column in 1968, expressing his sorrow at Jim Clark’s death. How true those words rang two years later.

The McLaren team went on to achieve everything Bruce had dreamed of – Formula One world titles, Indy 500 success, a successful road car arm. And the line that Bruce is most famous for? “I feel that life is measured in achievement, not in years alone.” He was even masterful at writing his own eulogy, it seems.

STORY Stephen Dobie