Road trip: to Alaska's Arctic limits in a Mazda MX-5

It's roughly quarter to six in the morning when I nearly run over a bear.

Or run into a bear, since the fuzzy hillock staring at me from 20 feet away probably weighs about the same as the MX-5 I'm driving.

We gawp at each other for a while, the ursine and the human, as confused as each other.

The bear wondering why a small, off-white roadster should have suddenly appeared in its remote territory north of the Arctic Circle, when the usual occasional traffic consists of easily avoided big-rigs, and me on the grey edge of hypoxia because I've forgotten to breathe.

I have the roof down. To a hungry bear, I probably look like semi-tinned dinner.

Very slowly, I reach for reverse, begin to crawl backwards out of pouncing range and promptly nearly hit the camera car.

Luckily, reinforcement seems to provoke a reaction, and the Grizzly whuffs mightily from somewhere in her sternum and ambles off into the trees.

At the opposite end of the respiratory spectrum, I gulp air like a drowning man.

Ten minutes later, I nearly run over several things that look like steroidal chipmunks, an adult beaver and a lynx – a cat the size of a labrador, with huge furry feet the size of my spread hands – and decide that the Alaskan wilderness really is dangerously full of wild.

And that it was a faintly ridiculous idea to try to drive the entirety of the Dalton Highway – and back – in a small roadster with the roof down.

It sounded like a jolly notion in the UK, but the chances of being messily attacked by the local fauna are somewhat less intense in rural England. You don't tend to get badgers as big as your car where I live.

There is method, of a sort, to the madness. The MX-5, like it or not, is considered to be a little bit sportscar-lite.

Something the hardcore wouldn't consider, because it's amiable and practical and doesn't try to vault you spitefully through the nearest hedge every time you make a minor mistake.

And yet, here we are. At the top end of Alaska, attempting to verify the little Mazda's intrepid credentials by doing something ridiculously rugged.

Of course, it's largely pointless, because you either get the idea of the MX-5 or you don't, but I happen to believe that brilliance isn't necessarily allied to scariness, that you don't need to buy cars exclusively using the currency of testosterone, and that the friendly little Mazda is more than capable of delivering proper sportscar fun no matter what the environment.

Which is why we're driving the new MX-5 up the James W Dalton Highway north of Fairbanks, Alaska, to the Prudhoe Bay oilfields on the edge of the Arctic Ocean, to prove that affable doesn't have to mean a lack of capability.

What it will mean is a proper adventure for this little car, because most people even bothering to attempt this road do so in, at the very least, an SUV, if not something with more than four wheels and its own water-purification system.

The road was built as a supply route for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System back in '74, is one of the most isolated roads in the United States, and one of the few I've ever driven where the tourism advice is to bring survival gear.

That's 666km of dirt and gravel road to the top, 666km back, plus a few hundred klicks of tarmac from Fairbanks.

For extra macho points, I would also carry all my own spares and fuel, and attempt the journey without closing the roof.

Because it's summer, and that's what roadsters are for.

Unfortunately, what I hadn't bargained on was that an Alaskan summer has an irritating tendency to rain. A lot.

And when you drive a non-tarmac road that is pretty much exclusively used by heavy trucks supplying industrial sites – the Dalton is featured on the popular TV show Ice Road Truckers – you find that you also subject yourself to quite a lot of mud. And ruts. And potholes.

Absolutely none of which are inherently kind to small, two-seat roadsters which some pillock has left defiantly open to the elements.

At this point, I wish to point out that this MX-5 is completely standard. As in completely. We're on 17in alloys and summer tyres, with a stock 2.0-litre, 158bhp, 148lb ft naturally aspirated engine.

The only things I'm carrying are a pair of spare wheels plus tyres, a couple of jerrycans of unleaded and a kilo of trail mix. Although it would have been handy if I'd also remembered to pack a jack.

Still, as my nose and eyes clog with mud and the car starts to shake like a badly balanced washing machine, I look forward to the next 1,000-odd miles with the same excitement I would normally reserve for a four-day bout of gastroenteritis or vicious street robbery.

At least I've got heated seats.

Honestly, it feels like being on one of those vibrating Victorian weight-loss contraptions.

Constantly jiggled and shuddered until my insides feel like foam.

The USB ports that charge my phone oscillate themselves from their slots every 20 or so miles – not that it matters, because there is precisely no phone signal anyway.

After some 50-odd miles, I feel a bit sick. It's not as if the view is particularly stunning, either.

Yes, the enormous twin barrels of the pipeline that shadow the road are fascinating for the first few miles, but weirdly, after a bit you start to get used to the scything black lines that scar the view, whose pump stations can move 754,000 barrels of oil a day.

The countryside is pleasant enough, though not an awful lot different to what we've enjoyed on the Elliott Highway out of Fairbanks – long, sweeping ridges furred with black spruce, aspen and birch.

If you like trees, there's plenty to get excited about. As in millions of acres of excitement. I can't get excited, because my eyes have gone numb with the jiggling.

First stop is the Yukon River Camp, and a chance to fill up with fuel and food, seeing there are only a couple of places on the Dalton that actually sell either.

The weather has turned grey, mist-filled and close, causing a particular kind of all-over wetness that slides into collars and pokes dead, damp fingers into unprotected seams.

There is no view as such, and Yukon River Camp can best be described as practical.

Because this area is protected, technically there can be no 'permanent' structures, so everything is constructed of a shambling Lego of trailers and Portakabins.

The petrol station is literally a tank of fuel with a hose attached, and the prevailing custom appears to be various species of grizzled trucker and a couple of hardy enduro bikers.

Bikers who – tellingly – turn around and peel off back towards civilisation after wondering why the hell I'm driving around in the rain with the roof open, and laughing at my mud-spattered face.

The truckers just grunt and look at me as if I have some sort of mild madness.

A couple of hours later, and I'm wondering the same thing. The weather has turned even more disagreeable, and things are less than pleasant in the MX-5's cockpit.

Not through any fault of the car – those heated seats really do work – but I've got a spare wheel and tyre in the passenger seat, a passenger footwell full of petrol cans, and freezing fog simultaneously obscuring the view and trying to burn my ears off.

There's also the torturous nature of the Dalton. Because it lies.

Basically, at certain points, the Dalton Highway has stretches of perfect asphalt.

A blessed relief after being generally beaten to a pulp by the ridges and ruts left by the heavy-duty traffic.

But they never last long enough, and serve to remind you how bad things are on the dirt in a low-slung sportscar when you inevitably drop back onto the ungraded bits.

And then there's the trucks themselves: giant chrome-laden titans, often dragging enormous loads, that Do Not Stop.

When one bears down from the distance, you'd better get the hell out of the way – especially if you're in a vehicle that might escape notice.

Beware, mind, because the margins of the highway are gravel, and when you drop your right-hand wheels into deep kitty litter at 50mph, you'd better be holding on. After the first few breathless games of slippery chicken, I slow down to pass.

It's tiring, hard work, this. A grind. We're headed to a place called Coldfoot, at milepost 175, but some 60 miles before we get there, we cross the Arctic Circle at precisely N 66c 33' W 150c 48'.

There should be some sort of change in the environment to jolly me along, but there isn't, just a sign and a load of tourists in an all-wheel-drive tour bus who take pictures of the crazy person in the mud-brown MX-5. It's still raining. I feel no sense of accomplishment whatsoever.

Several hours later, we arrive in Coldfoot, realise that our 'hotel' looks like the kind of place featured in the title sequences of a movie where everyone dies, and get a bit sad.

I knew it was getting bad when I failed to smile as we passed Gobblers Knob.

Next day, and after a fitful night's sleep, we meet the bear and the lynx, and it buoys us. We track through the 'pingo' field below Sukakpak Mountain – a weirdly Arctic phenomenon where meltwater gets into the permafrost and splits the soil, making it look like the surface has lightly exploded, head up into the Brooks Mountain Range, pass the last tree on the Dalton Highway (it gets its own sign) and head up the Atigun Pass.

The Atigun is significant. Mainly since it's snowing, I'm on summer tyres, and this is the highest pass in Alaska, at 4,739ft. I also still have the roof down, and the temperature has dropped to -15C.

It's also important because this is where we cross the Continental Divide: rivers to the north empty into the Arctic Ocean, while rivers to the south empty into the Bering Sea. We're heading into the tundra proper.

Again, I'd like to say at this point that I'm filled with the awe of adventure and manage some Bear Grylls-ish wonder at the magnificent outdoors.

But I'm not. I'm filled with the need to survive until the night-time, and the neednot to crash or break down in a place where rescue and medical services are several hours away.

The MX-5 has taken an absolute beating and, apart from having several kilograms of mud throwing the wheel balance into fits, it's simply doing what it needs to do. Which, in several instances, involves drifting around snowy bends on the side of cliffs.

Believe me, I wouldn't be happy doing that in anything else. So 160-ish horsepower isn't that much, but with the standard-fit LSD working hard and rear-wheel drive, the MX-5 provides the kind of fun that doesn't leave you upside down in a ravine at the end of it. It's utterly, utterly brilliant.

Unfortunately, only a few miles later we're also some 350 miles into the journey on the other side of the pass and driving across completely flat Arctic tundra with all the distinguishing features of a large brown carpet. It's heavy with fog, alternately snowing or raining, and desperately miserable.

We pass a place called Happy Valley – basically a collection of huts – and I can't think of a less appropriately named area in the entire world.

There's nothing here, just a fog-laden hint of a horizon, various shades of brown and a neon-speckled man on a unicycle.

Hang on a minute. My brain slows to a crawl. I just drove past a man on a unicycle down a mud road across the Arctic tundra several hours from civilisation. Handbrake, one-eighty, let's see if I'm hallucinating.

Five minutes later, and my own sanity is confirmed by the reality of Sid, who really is riding a unicycle down the Dalton.

He flew into Prudhoe Bay, some 80 miles north, and is unicycling down the Dalton on his way to Montana. That's 3,000 miles away.

This is momentous news. Mainly because I realise I've just driven over the Atigun Pass and thought it was hard and Sid can't even freewheel down the good bits.

We chat for a bit, and it turns out that our monocyclist is doing this for adventure's sake. Because he enjoys it.

And it's enough to make you feel better that the human race still contains the kind of people who do crazy things just because they can.

Sid also mentions that he thinks I'm insane for driving a car like the MX-5 up here, never mind with the roof down. We find solidarity in our stupidity, and I leave him to continue.

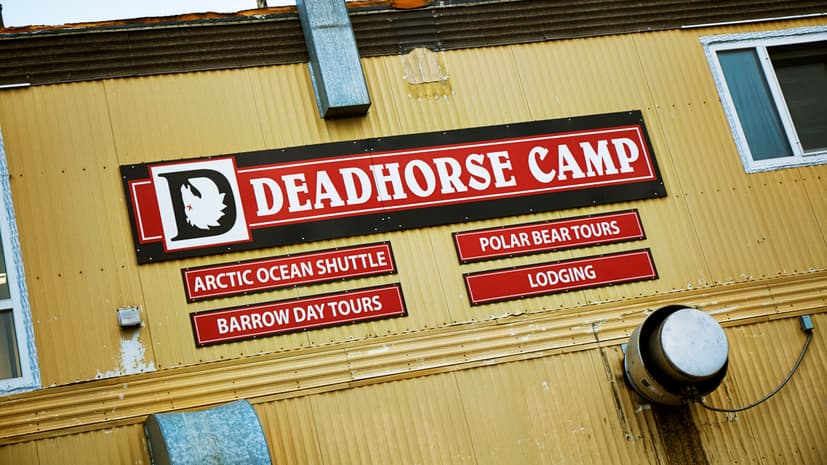

Arrival at Deadhorse at the bottom of Prudhoe Bay is achieved late in the evening. Again, the accommodation and dining facilities are loosely based on the idea of an oil rig, and that's basically what they are – Deadhorse only exists to support the pipeline and oilfield operations in the bay.

It has a permanent population of just four, with a part-time complement of between three and 6,000 people.

There are a lot of bearded, muscular men with forearms like scaffolding poles. Most of whom laugh at the MX-5. Alcohol is banned. You can guess why.

We attempt to get to the coast, but as it turns out, the final section of the road is actually owned by the oil companies, and we are forcefully thrown out by a BP security guard, who – in a fit of bored pique – calls all the other local security guards to tell them to watch out for us and bar passage.

We're pretty easy to spot, and there's not much to do in Deadhorse at night, so we retire early and prepare for the monotony of the return journey the next day.

I could mention the toilets that have nothing but a short shower curtain separating you from other occupants of the shared bathroom here, but I'm still too traumatised to recall it.

Morning dawns, and I trudge to the car weary and beaten; the return trip promises the reflection of the outward, and I'm not looking forward to it. But the sun is finally out, and it's like God's own magic trick.

The veil has been pulled back on Alaska. The sky is brochure blue and film wide; so incredible it seems almost artificial.

Suddenly, the monotonous brown velour of the tundra becomes some sort of Zen canvas on which to paint your imagination, full of subtle colour and hidden life.

The Franklin Bluffs on the side of the Sagavanirktok River are basically Martian shades of yellow and ochre – due to the iron-rich soil – and the landscape is sluiced with hundreds of small rivers and lakes that slide over the flat vista like mercury.

It's also hot. Like 22C hot, and the sun is shining. And the MX-5 feels' triumphant.

It's the most appropriate, best car for this journey at this point, and I couldn't be happier. All that pain and discomfort, just for a few minutes of this, would have been worth it.

But we don't get just a few minutes. We get hours of intense beauty.

The day is a blur – literally as well as metaphorically, unfortunately, because the bumps haven't evaporated – but still something best described in the style of a gratuitously overwrought Victorian novel.

We catch up with Sid – he's done another 35 miles – and give him biscuits.

The tundra, even given its simple nature, is radiant. The Atigun Pass is splendid.

All of it lounging in sun, and a breeding ground for superlatives that don't seem quite big or spectacular enough to encompass the punch in the guts some of these views contain.

One piece of road that swoops regally down a valley and then up into the Atigun is eternally shadowed by the slithering pipeline, and beautiful enough to make you have to take a moment.

And the view is a thief. It steals a piece of your heart and never gives it back. We sail through the day, running on compressed awe and cheap coffee, constantly shaken and beaten, but elated.

The air tastes fresh and clean, wild and green, and there's no better way to experience it than in a little roadster exposed to every scent and sight, an endless joy of impossible things.

We get to Coldfoot, and the Portakabin hotel feels like a palace. The food tastes like manna. We have seen the Arctic at its best, and it is dazzling.

The next day isn't quite as spectacular, but it's still fresh and sunny, and in between doing a little light fishing in forested lakes where swarms of pigeon-sized mosquitoes try to bite your face off, we drive, and refuel the Mazda at the side of the road.

I spill petrol on my feet and spend the day smelling like an accident waiting to happen, but nothing can dent the mood, and the forest becomes something from a fairy tale, a full Pantone chart of greens broken by vibrant reds and golds and rich, earthy browns.

There are eagles and ducks and geese and funny-looking squirrels that come barrelling out of the undergrowth like suicidal doormats.

We rewind the journey, but the song isn't the same the second time around. It's joyous and full, and completely satisfying.

Back to Yukon River Camp, back to the Elliott Highway and back to a proper road where somehow the spell is broken and it feels like we're back in civilisation.

Phones happily chirp their connections, emails torrent into inboxes in a fanfare of modernity, and we're done.

Once we're back in Fairbanks, it takes hours to clean the Mazda up into some semblance of order.

There's mud concreted into the wheels, and the only vaguely presentable part of the interior is the seat covered by my body.

But, as we drive back to return the car, the little MX-5 is as fresh as when we picked it up.

It's been on a journey that most balk at making in a full-house off-roader, and it never missed a beat.

Delivered fun in a way that made me feel safe, skipped where other cars would have tripped, and became a companion rather than a vehicle.

Not a hardcore sportscar? Not from where I've been sitting.

And when the Arctic decided to bring its full majesty to bear on that couple of sunny days in October 2015, I swear, on my life, there wasn't a better seat in the house.

STORY Tom Ford

PHOTOS John Wycherley