16 of the fastest production supercars you've forgotten about

Vencer Sarthe

First things first: the name. Vencer, it seems, means ‘win’ in Portuguese. But this car isn’t Portuguese, it’s Dutch. Maybe ‘Winnen’ was taken by another brand? Maybe it was too literal for English speakers? We just don’t know.

In any case, this supercharged 6.3-litre V8-powered supercar definitely has an international flair – Sarthe, as any endurance race fan will roll their eyes and explain to you, is the circuit at which Le Mans endurance races have run since the 1920s.

But the Sarthe name also hints at its inspiration and intention – Vencer boss Robert Cobben first stood at the Mulsanne Straight as a teenager in the 1980s, watching sports-prototype cars blitz past at more than 355km/h. Needless to say, it had something of an impact.

As for the intention side of things, you’ll find 622 Hennessey-fettled horsepower’s worth of it, with full carbon-fibre construction and a 6spd manual gearbox. Oh yes, this is a supercar of the old-school ilk – no traction control, no automated gearboxes, no active this or slip-control that. Just power, lightness and ABS for when you find that all that power and lightness has put you in a situation you’d rather not be in.

Tramontana XTR

As for Tramontana? Well, that name refers to a wind that brings inclement weather. Or, if we wanted to be a bit more lyrical about things, we could call it the Storm-bringer. Because nothing’s cooler than names that sound like they belong in Conan the Barbarian.

Anywho, you’re probably wondering when we’re going to mention the… er, polarising design. And, unless we’ve missed something, that would be about now. It certainly is a lot to take in. We suppose the most measured thing we can say is that buyers of 880hhp supercars with tandem seating and F1-style suspension aren’t really in the business of being wallflowers, are they?

Ascari KZ1

Three cars in and we’re already back to the Dutch. It seems that they do one hell of a line in off-brand supercars, doesn’t it?

Technically, this one’s British, as Ascari was founded in Blighty. But then again, it was named for Alberto Ascari, and he was about as British as he was a halibut. What he actually was, in fact, was a wondrously talented Italian race driver who was just as adept on two wheels as four. So basically John Surtees with a continental accent.

The Ascari KZ1 posted a 1:20.7 on a damp TG test track, putting it ahead of the times set by the Gallardo Superleggera, Mercedes-McLaren SLR and the 997 GT3 RS in the dry. So, potent enough, you’ll admit.

And, much like its Dutch brethren, the Vencer Sarthe, it’s all carbonfibre, and there’s nothing in the way of electronic nannies to hold your hand and clean up your messes. If you get it wrong, about 500 horsepower’s worth of BMW V8 will happily show you the error of your ways. And then some grass. And possibly the side of someone else’s shed.

Arash AF8

While the company behind the AF8 has gone by a few names, we’re pretty sure that Arash – the name of a heroic archer who loosed an arrow that flew the distance of 40 days’ walk – is probably the best. Helpfully, it’s also the first name of the man who owns the company.

The AF8 is a properly serious bit of kit, too – tubular steel chassis with bonded carbonfibre sections, and 550 horsepower’s worth of Corvette-sourced LS7 V8. Yep, that’s the 7.0-litre one.

When you factor in that there’s just 1200kg to motivate, it’s little wonder that zero to 95 is apparently said and done within 3.5 seconds and 320km/h is within reach. And, for anyone who says figures like that are a little old-hat or ho-hum, we defy you to experience either the former or the latter in person and then return the same verdict.

Venturi 400 GT

For a long time, we’ve made fun of the PRV V6. That could just be because of its inclusion in the DeLorean, a car so slow and wet that Doc Emmett would struggle to reach 140km/h, even if he had 1.21 gigawatts, a flux capacitor and a dog named after a famous scientist.

But the Venturi 400 GT might be what finally sets the record straight about the much-maligned motor of malheur. Although a cure for motoring writers’ obsession with alliteration may never be found.

Moving on. In the 400 GT, the generally weedy PRV V6 made a genuinely gobsmacking 400hp and 530Nm. To get there, Venturi compiled a greatest hits version that was so good, it really made the individual albums unnecessary. There were 24-valve heads, as opposed to the standard 12 – courtesy of Peugeot – and the low-compression, high-turbo-pressure combo pioneered by Renault. We presume that Volvo kept doing Volvo things, like moose tests and sauna sessions.

The 400 GT weighed just 1200kg, so 400 horsepower was more than enough to crest 100km/h in less than five seconds and punt past 270km/h. Cue the now unavoidable cliche: Mon dieu!

Toyota GT-One

If you give a car company’s motorsport arm anything resembling a loophole, they will absolutely exploit it. Case in point: the GT1 class in endurance racing, which gave us ‘road cars’ like the Porsche GT1, Mercedes CLK GTR and the Toyota GT-One.

Homologation rules stated that there had to be a road-going version of any car entered in GT1 competition, but stopped short of suggesting how many examples of said road-going car should be built. As loopholes go, it’s one you could pilot a cargo plane through.

Although they could have stopped at just one, the generous bods at Toyota made two road-legal versions of the 600hp, 900kg, Dallara-designed race car, with road-going concessions extending as far as catalytic converters, raised ride height and a slightly smaller spoiler. If you think about how hard Ferrari worked to turn Alain Prost’s Ferrari 641 into the F50, then consider the Toyota GT-One road car the antithesis of that.

Our favourite part of the ‘yeah… close enough’ homologation rules at the time was the requirement that the cars had luggage space for a ‘standard-size’ suitcase. Toyota merely made the GT-One’s fuel tank large enough to fit the suitcase, then convinced scrutineers that, because the car is inspected without fuel, that this adhered to the rules.

Pictured: the racing GT-One

Nissan R390

Styling by Ian Callum, engineering by Tom Walkinshaw, a 3.5-litre, 550hp V8 and provenance from the bonkers (and short-lived) GT1 class of endurance racing? As America’s founding fathers (probably never) said, fetch us a damn quill, because we’re signing right up.

That’s right; not to be outdone by its homegrown rival, Nissan decided to have a full-blown tilt at this whole ‘make a race car and then convince the scrutineers that it’s a road car’ lark. So competition-spec tech like an Xtrac 6spd sequential gearbox and six-piston AP Racing brakes were counterbalanced by leather seats and an actual dashboard. A flawless ruse, we’re sure you’ll agree.

The chassis was a development of the Jaguar XJR-15, the tail lights were from a Fiat Coupe and there was a rumour that there was only ever one Highlander… er, R390 made, and that Nissan’s claim of building two was really just building one, then converting it to a long-tail version. It was a bit of a hashmagandy to say the least.

But, in race spec, the R390 was more than a little potent. It’s probably best to put that down to Tom Walkinshaw Racing, of course, but there’s no arguing with all four R390s finishing in the top 10 at Le Mans in 1998.

As for getting hold of an R390 road car? Other than buying out Nissan in its entirety, you’re not going to have much luck.

Bristol Fighter

But how can you talk about difficult-to-buy cars without mentioning Bristol? That should have been translated into Latin and affixed to the badge of the few hundred cars it actually made over the 75 years in business. ‘Difficile Emere’ kind of has a ring to it, doesn’t it?

Usually, the rest of the world shrugged and got on with their lives, leaving Bristol’s staff to potter in their victory gardens or whatever they actually did in between building three cars a week for men whose beards had tweed jackets.

But then came the Fighter: gullwing doors, aluminium body, carbonfibre panels… this was not the Bristol we were used to. Well, to be fair, we weren’t really used to any Bristols, given that Bristol didn’t really do press cars, or PR, or anything else that gave the impression that anyone in the company was in the business of actually trying to sell cars.

In any case, Bristols seemed to have an air of old money about them. Buying a Bristol wasn’t just about fronting up to the Kensington showroom with a pocketful of cash; you had to win the approval of Bristol boss Tony Crook to even get on the list for a new Bristol.

But let’s say you did get into his good graces and got on the list for a Bristol Fighter – what would you get? Well, the 8.0-litre V10 engine from a Dodge Viper, tuned to produce 525bhp and 711Nm, and fitted into a narrow, British-hedgerow-friendly package.

You would also get to ninety-five klicks an hour from rest in about four seconds and, Bristol claimed, a top speed of 338km/h. That was probably down to the alleged 0.28 drag coefficient, which is only slightly less slippery than a greased eel. For a more helpful comparison, the Dodge Viper that shared the Fighter’s engine and gearbox has a Cd of 0.45.

Hm. Wouldn’t have minded a go in that one.

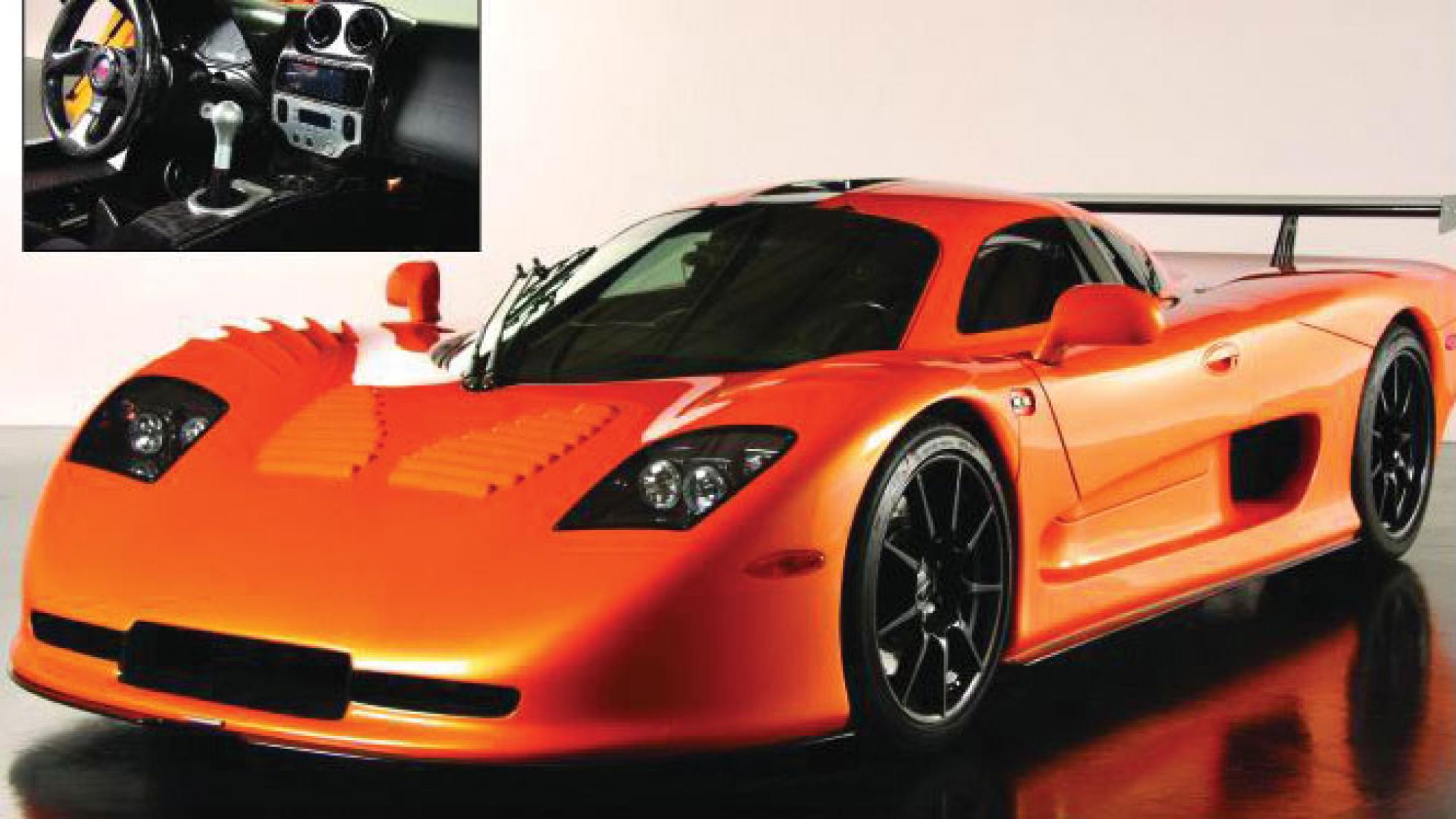

Mosler MT900S

What do supercars and post-Keynesian modern monetary theory have to do with each other? Well, two things: Warren Mosler, and a searing headache when car journalists try to understand what, exactly, post-Keynesian modern monetary theory actually is.

But that’s no such problem for Mr Mosler, who made a career of figuring out the maths behind the stock market madness, then parlayed his winnings into some of the ungainliest, yet fastest cars you’ve ever come across.

And we say neither of these facts with even a hint of embellishment – the Mosler Raptor (nee: Consulier GTP) was banned from the IMSA series over in the US of A after it consistently beat 911 Turbos and Callaway Corvettes. And to look at it was to wonder if it was a race car or a prototype droid for an upcoming Star Wars flick.

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that George Lucas himself was the first to receive a production MT900S, the first Mosler that actually looked worthy of a wall poster – black on black, in case you were curious.

Although the colour is perhaps less important than the sub-1100kg kerb weight and 435bhp V8, which combined to run the 0-95 gauntlet in just over three seconds – faster than the contemporaneous Porsche Carrera GT and Ferrari Enzo.

Oh, and in true Mosler fashion, the MT900R racing version won the 2003 Daytona 24 Hour race. So while the ugliness went by the wayside, it’s clear the pace didn’t.

Dauer 962

But it’s hard to talk about endurance racing without thoughts immediately turning to Porsche. Its 962 racer is arguably one of the greatest endurance racers ever built, and its list of drivers is pretty much a greatest hits of Top Gear’s ‘Would like to (or would have liked to) share a whisky with’ list – Jacky Ickx, Stefan Bellof, Derek Bell, Jochen Mass, Mario Andretti – and some bloke called Tiff who used to work for Top Gear way back in the day, apparently.

It also spent time in the hands of another bloke who didn’t work for Top Gear, but probably would have fit right in – Jochen Dauer, 1988 European Sports Car Champion and 962 aficionado, to say the least.

After his racing team started to struggle and eventually withdrew from competition, he consoled himself by converting a Porsche 962 into a street-legal car. Needless to say, we have deep respect for ideas of such harebrained genius. Apparently, Dauer did such an excellent job converting the 962 he had from his racing days that Porsche got involved.

Why? Well, as a road-legal car, it could enter Le Mans in the GT class, rather than the dying Group C. Yep, it’s a race car masquerading as a road car, entered in a modified road-car class in endurance racing. Anyone else wondering if this was the kernel of the idea that eventually culminated in the 911 GT1?

Anywho, as a bona fide race car, the Dauer was the kind of quick that’s difficult to explain without torturing at least one metaphor, but we’ll give it a crack: it won Le Mans outright in 1994 and was promptly banned from the 1995 race.

Now think of this kind of performance – Porsche 935 turbo flat six, 0-95 in 2.6 seconds and 405km/h top speed – in a road car. Metaphors can breathe easy when you have facts like that.

Jaguar XJR-15

Hmm. Perhaps we should have called this list ‘A bunch of race cars made road-legal that you may or may not remember’. Because it sure seems like that was the hypercar du jour of the 1990s, doesn’t it?

And, just like the Dauer 962, the XJR-15’s origins are rooted in the truly excellent topsoil of Group C. And, it must be said, the XJR-15 sprung from an exceptionally fertile patch, worked by Tony Southgate at Tom Walkinshaw Racing.

In our book, the XJR-9 is up there with the very greatest things that Jaguar has ever done – winning both the Daytona and Le Mans 24 Hour races, claiming the 1988 WSP Championship and handing Martin Brundle the driver’s championship.

So it’s the kind of car that you’d a) assume would pretty much rule the streets and b) pretty much destroy your eardrums. And your assumptions would be pretty much spot on – Brundle himself has said that when the XJR-9 started up, people nearby would jump.

You know how people sometimes talk about ‘a race car for the road’? Jag took that one pretty literally in the case of the XJR-15 – it’s basically an XJR-9, with a bit more room in the cockpit, air con, pop-up headlights and the bare minimum of modifications to make it road legal.

It really is so close to the XJR-9. It’s wild, feral and just as frighteningly loud. Luckily, Jag would supply two pairs of microphone headsets, so you could still manage a conversation with your passenger. Luxury.

Lister Storm

Cast your mind back to 1993. Or, if you weren’t alive in 1993, prepare to have a bunch of things you don’t remember or care about trotted out for the benefit of stoking nostalgia in the old folks.

Bill Clinton had just been sworn in, Jurassic Park had just come out and the Czech Republic and Slovakia had just parted ways, saving millions of school kids the trauma of trying to spell Czechoslovakia in fourth-grade Geography class.

It was a pretty heady time for supercars, stock market wobbles or not. In fact, the late 2010s really reflect the early Nineties quite well – all sorts of companies are putting out (or at least promising) obscenely fast supercars with power figures that seem more applicable to nuclear facilities, materials that seem straight from an Arthur C Clarke novel and price tags that remind us that the gilded age never really went away.

To wit, we present the Lister Storm: a 335km/h supercar with 554hp and 790Nm – and four seats. Yep, it was the fastest four-seat supercar for about a decade, thanks in no small part to a race-spec Jaguar V12, bored and stroked to 7.0 litres.

It was basically the engine that took the XJR-9 to victory at Le Mans, enlarged by another litre and then wedged in the middle of… well, a wedge. Man, 1993 was just as awesome as we remember it.

Cizeta V16T

Figures and stats so very rarely give a proper indication of the scope of a situation. It’s a lot of what, without any how or why, which is what tends to matter in life. That is, unless the ‘what’ in question has 16 cylinders, eight camshafts, four cylinder heads, two fuel-injection systems and two timing chains. And presumably a partridge in a pear tree.

Yes indeed, it’s the singular powerplant that drives the Cizeta V16T, which, despite six litres of displacement and 16 pistons, revved to 8000rpm, where it made 548hp.

If you’re thinking, “Boy, that sure looks like a Lamborghini Diablo”, you’re not far off; it’s what Marcello Gandini originally envisaged for the Diablo, before then-owners Chrysler softened and rounded the edges in the final product. And it was put together by ex-Lamborghini staffers after Chrysler took over the company.

If you’ve been around the traps a bit, you might remember this car being called the Cizeta-Moroder. That’s because famed composer Giorgio Moroder (who should probably be crowned the King of movie scores, purely for his work on Scarface alone) put his time, effort and money into the project to make it a reality. But, as is the way with these things from time to time, bad blood ensued. So it’s just Cizeta now.

Lotec Sirius

Once you start drilling down into the properly rare supercars, the story tends to go one way: someone hatches a great plan to build a new supercar, then sets about their labour of love. It sells about as quickly as used sheets of toilet paper, while Ferrari and the elite crew sell about as well as toilet paper in a COVID pandemic.

At some point, the money runs out, the good will of the financial backers runs out, and the net result is an empty, forlorn factory with a few bits and pieces gathering dust, and a number of actual, running and registrable new supercars that you could count on your fingers. If you’d had your hand cut off for thieving.

And with that preamble finished, let us now introduce the Lotec Sirius. Apparently, it’s ‘Lott-ek’, not ‘Low-tech’, but it’s still a bad name. Hey, it happens.

But the Sirius – named after the brightest star in the sky – did have something of an ace in the hole: a twin-turbocharged, 6.0-litre V12 that apparently churned out 1200bhp and 1315Nm. And it’d hold together doing it, because it was a tweaked Mercedes unit from the S600. And any number of tuners have gotten ridiculous figures from Merc engines.

The top speed, depending on gearing, exceeds 400km/h, or comfortably enough to make you wonder how well the steel space frame chassis has been welded. But that’s really only a problem for one person, given that, as far as we know, just the one Sirius has been built.

Marussia B2

For quite a few years, a Russian supercar was one that worked.

Such was the unremitting awfulness of the Soviet car industry. But now that we’re three decades clear of the Soviet Union, we can talk about Russian supercars without even the faintest of wry grins or bad jokes manifesting.

OK, just one more bad joke. A man pulls up to a service station and asks the attendant: “A set of windscreen wipers for a Lada?” The service station attendant replies, “Yeah, sounds like a fair trade.”

But let’s make one thing perfectly clear: this was not the state of affairs with the Marussia B2, which had engines by Cosworth – including a 2.8-litre turbo V6 with 425hp and about the same in torque, because, well, Cosworth. Combine that with an 1100kg kerb weight and the claimed performance is impressive: 3.2secs to 95km/h and a top speed 340km/h.

That’s all well and good, but any number of cars will deliver that sort of performance these days. We need something to set the Marussia B2 apart. Like the fact that the man behind the company, Nikolai Fomenko, was a part of the Russian version of the Beatles, the host of the Russian version of the Top Gear TV show and sponsored a Formula 1 team. That’s the kind of provenance you won’t find in just any auction listing.

With Marussia done and dusted, the chances of getting a B2 are slim. But the chances of getting another rubbish but slightly applicable joke are quite good – “Hey Dad, can I have the keys to the car?” “Sure, but don’t lose them; the car will be here in just seven more years!”

Ultima GTR

What is it, exactly, that makes Britain such a font of low-volume sportscars? Is it our abundance of tracks? Abundance of sheds? Abundance of blokes who are a bit handy with fibreglassing?

Someone much cleverer than we are probably has the actual answer to that question, but we’re going to fob that off in favour of the usual British response: because we felt like it.

And this razor can, at least on the surface, be applied to Ultima. Why did Ultima build a record-shattering car, only to offer it in kit form? Felt like it. Why did Ultima build a road-going space-frame racer, then give it those supercar folding doors that are made for Monaco, not maximum attack? Felt like it.

Of course, these aren’t the actual answers to these questions. And, if you found a man with a beard shaggy enough, we’re sure he could give you the answer through his adenoids.

Instead, let’s roll out a few of the Ultima GTR’s records, claimed back in 2006: fastest 0-95 and 0-160 times in 2.6 and 5.3 seconds respectively. Nought to 160km/h in 5.3 seconds is… heady, to say the least.

One hundred and sixty back to nought in 3.6 seconds is enough to move the molars to the front of your mouth. And this is without ABS, by the way, because the Ultima GTR doesn’t have it. Or traction control. Or launch control. Or power steering.

STORY Craig Jamieson