AI might doom us, but it’s making racing games better

Artificial Intelligence might doom us, but it’s making racing sim games better

Until surprisingly recently, racing offline opponents in driving games was more like trying to beat a train around a track than besting a rival driver. The AI wasn’t in control of its vehicle in the same way you were. It was effectively on rails.

A game designer drew out a racing line during development, and the AI cars followed it forevermore, applying throttle and brake inputs exactly when instructed according to that designer’s ideal lap, and only deviating from it when you went barrelling in and forced them off line.

When that happens, the AI drivers simply tried to get back to the ideal line as quickly as possible. If a human’s pushed off track, they’ll generally cut the next five corners in a fugue of righteous adrenaline.

Videogame opponents just quietly righted themselves and got back to it. And that made offline races a processional affair with a whiff of inevitable player victory. It was just a bit boring.

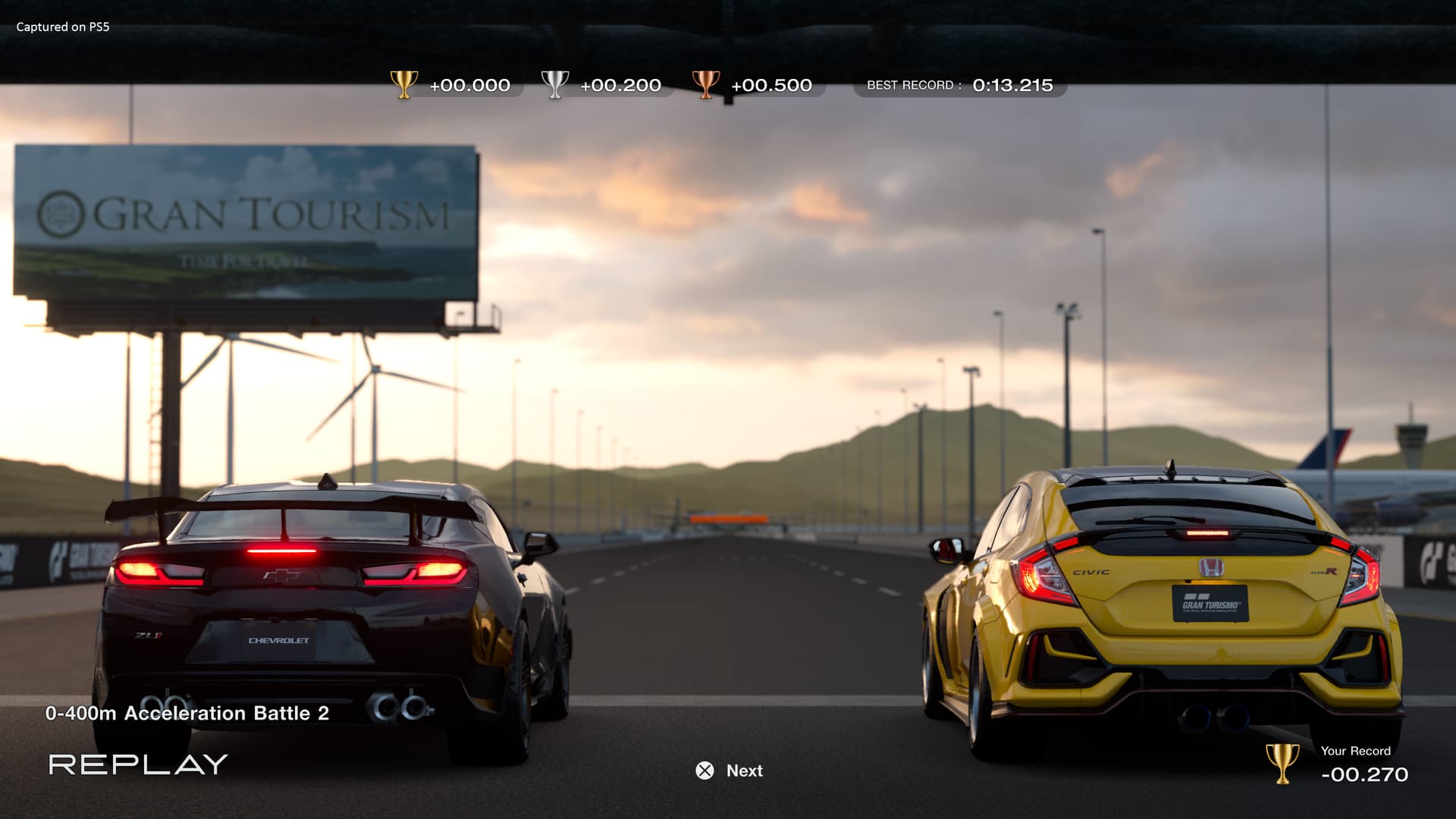

But the way racing game developers have started building their AI drivers using deep learning AI networks has totally disrupted that status quo. Polyphony’s Gran Turismo 7, Milestone’s MotoGPseries and Turn 10’s Forza Motorsport all employ learning AI to make the competition smarter and the racing more unpredictable.

These might very well be the neural networks we look back on, huddled around a bin, roasting our shoe leather dinners over a pile of burning family photos, saying if only we’d stopped it back then. But for now, at least, they’re making racing games much more exciting.

Sony’s AI research division worked on Gran Turismo’s ‘Sophy’ AI for years, in partnership with several universities’ own AI research teams. They used thousands of PS4s, all running Gran Turismo Sport, and built a different kind of videogame racing driver.

The team called this process mixed-scenario model-free deep learning using quantile regression soft actor critic, and as much as that rolls off the tongue let’s just keep referring to it as Sophy.

Instead of adhering to a predetermined racing line that a human programmed for it, Sophy was instead given a huge amount of information about the car it was in and the track it was driving around, and incentivised to lap as quickly, professionally, and efficiently as possible.

That information includes the car’s velocity (including forward momentum, angular velocity and turning speed), acceleration, tire load, slip angles, track progress, surface incline, orientation on the track, upcoming course markers (regular internals indicating the left and right track limits and the centre point), and information that tells the car when it’s colliding with a barrier or it’s gone off course.

That’s enough information for Sophy to drive extremely quickly round a given track, but Sony and Polyphony didn’t just want speed. They wanted driving behaviour that feels human, that reacts to other drivers, employs strategy to overtake and to avoid being overtaken, and is capable of making mistakes.

So with that in mind, they rewarded Sophy for making each overtake and applied a penalty for each time it was overtaken. Interestingly and somehow terrifyingly, the team had to intervene and tweak these conditions because at one point Sophy was simply overtaking and allowing itself to be re-taken by the same car over and over again to get the overtaking reward.

But the fruits of all that deep learning are pretty evident. Gran Turismo 7’s AI drivers jostle for positions in ways their PS3 ancestors couldn’t have imagined. They still can’t do anything about you turning up to a Sunday Cup race in a 900bhp track car and absolutely smashing them, but that’s more of a bureaucratic matter than one of on-track smarts. Still: your move, Sophy.

Meanwhile in Italy, Milestone’s licensed MotoGP games have been employing similar techniques to make the virtual versions of Marc Marquez and Fabio Quartararo just as dynamic and unpredictable as the real riders. Like GT’s Sophy, Milestone’s riders are given information and objectives and then given the freedom to figure out the fastest way to lap a track and overtake other riders, instead of being spoon-fed racing lines and overtaking protocols.

The inputs are even more complex in a motorbike sim: two separate brake inputs that affect the bike differently, progressive lean angles that require more than just stabs of left or right to achieve, and the risk of not just traction loss but wheelies on corner exit.

As such, you often see riders make mistakes in MotoGP 23, just as you see the world’s very best riders routinely tuck the front or out-brake themselves during a race weekend. You’ll see five riders all taking slightly different lines though a sequence of corners. And the racing’s all the better for it.

We’re about to see a massive jump forward in Forza Motorsport 8, too (Microsoft just calls it Forza Motorsport, under the mistaken impression that dropping the 8 makes it cooler). Previously in the series, AI cars couldn’t even hack modulated throttle and brake inputs.

You could see them blipping the brake pedal, putting on a light show at the back, in order to simulate a progressive braking curve, and they’d be rapidly on and off the throttle on corner exits too for the same reason. They had a grand total of three lines per track to drive on.

The upcoming game’s AI drivers do things differently. Like GT and MotoGP’s AI, they’ve been trained with information and objectives rather than routines. They’ve driven the tracks 26,000 times, and developed about 85 different racing lines across each circuit as a result.

So we should see them pushing track limits in perfect conditions, and then driving more conservative lines when their tyres are cold, or when the rain sets in.

It’s not all deepfakes and sector-wide redundancies, then. AI’s doing at least some good, even if that good is happening in the racing games we’re using to distract ourselves from a fearsome pace of change that threatens our way of life in ways we’re still trying to comprehend with each passing day. Silver linings and all that.

Maybe we can all just upload ourselves as virtual drivers when all our jobs are gone.

STORY Phil Iwaniuk