Geek out on the Murray T.50's amazing details

Titanium pedals

Gordon Murray is sitting in the T.50. I’m kneeling at the door. Feels kind of like I’m worshipping at the altar. And today’s first reading is taken from the book of pedals.

“I did the stress calculations for the pedals, and I said to the designer ‘look at the F1 pedals, but you won’t get them any lighter’. But then I decided to have a go too, and I realised the anti-slip you need for regulations could be the sharp edges of the pedal. As a result these are 300 grammes lighter.”

Gordon Murray is telling stories. Most of them include the word ‘kilogram’. The really special ones, ‘gramme’. Once he even mentions tenths of a gramme. He wouldn’t deny being obsessive about weight, but the word I’d choose to use is ‘evangelical’. Fits better with the quasi-religious symbology.

Here is a three-seat V12 hypercar that weighs less than a tonne. But weight is only one facet to the car and to Murray’s quest for engineering perfection. Because, like all car brands that have a messianic figure at their head (see also Horacio Pagani and Christian von Koenigsegg), the car reflects the man.

So here, in his own words, is Gordon Murray on his new car.

Chassis plate

While he’s sitting in the cockpit I ask Gordon to point out some other interesting bits. “Well, I like to think that everything is engineering art. There’s a fine line between engineering beauty and bling, and there’s nothing poncy in here. Everything is bespoke.

The F1 was about 98 per cent bespoke with a few carry over switches and air vents and some of those switches have a little bit of play in the spindle which I hate, absolutely hate, and the haptics on the switches were a bit too soft.

This time we’ve started from scratch with a company that makes aero parts. They cost a fortune, but now the haptics are absolutely spot on. I kept saying to the designers, ‘think high end camera’, but even the bits owners will never see are a work of art.

“One thing we have let them see is the chassis plate. It’s mounted just in front of the gearlever, but we’re actually sending it out to customers very soon in a presentation box as it’s a good piece to show what we’re all about.

It’s made from titanium and 4.5mm thick, so it looks heavy, but when you turn it over it’s been milled out to just 1mm thick from the back, so weighs just 7.8 grammes. You hold it in your hand and can’t believe how light it is.”

Touchscreen? Nah!

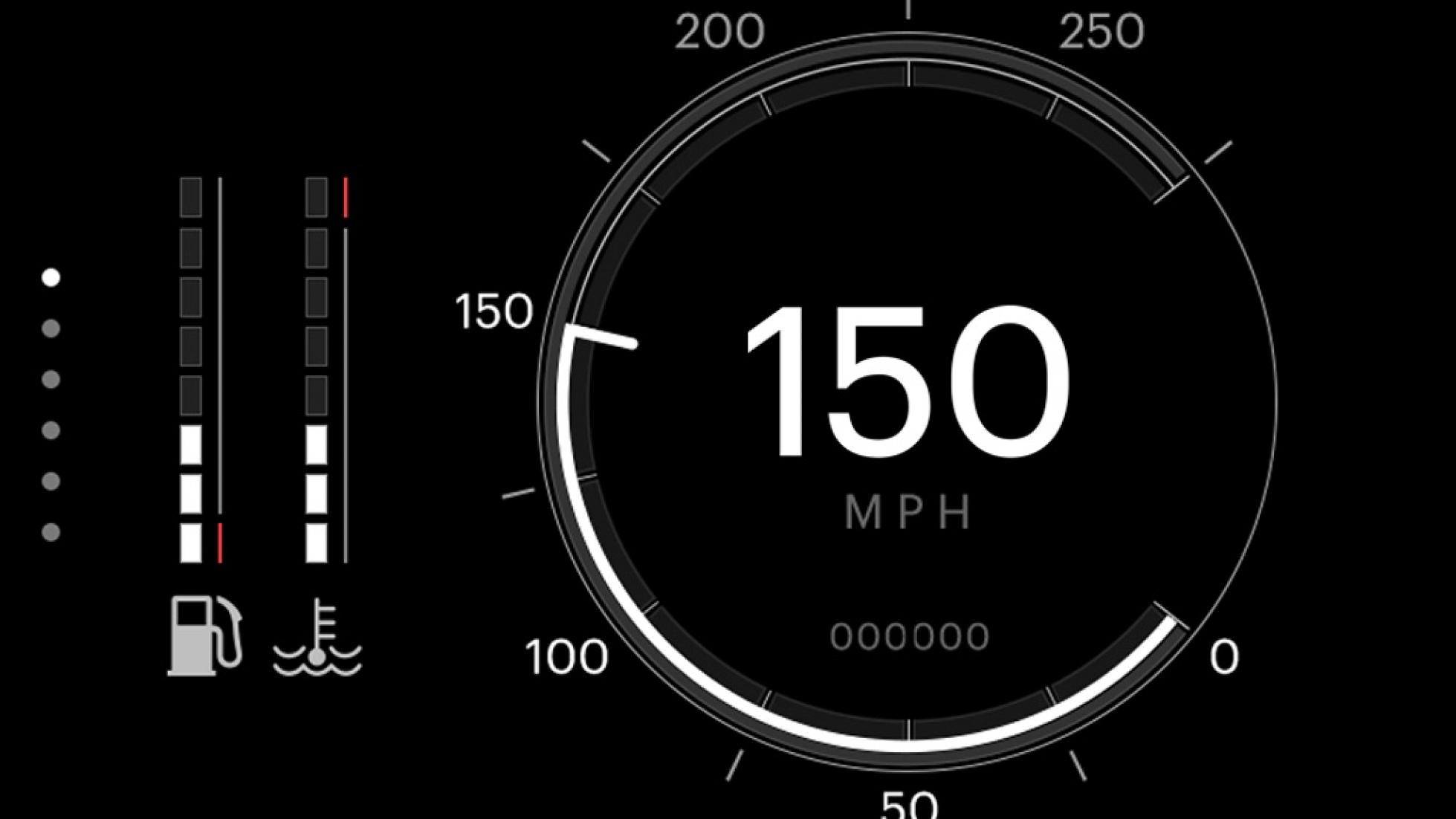

“Touchscreens shouldn’t be allowed in fast cars. Trying to jab at a screen when you’re driving quickly is absolutely ridiculous.” Instead the T.50 uses small, simple clickwheels on the steering wheel to control the screens either side of the central rev counter. The right hand side is for sat nav, media and infotainment, the left houses car, engine and aero information. Airvents are hidden under the screen hoods.

“There are no fancy dancing graphics on the screens – it took a lot to hammer that home with the supplier – I just wanted simple, clear white-on-black information.”

Famously, the F1 had a lightweight Kenwood hifi, “it weighed 8.5kg. We’re working with Arcam this time and the whole thing - amp, 10 speakers and 700 watts of power - is just 4.3kg.”

Seating position

“We had three different seating bucks and I think we had 43 different people getting in and out. It’s not easy on the F1 as we had the main carbon chassis spars running down either side of the driver’s seat. This time round I’ve moved them to a more conventional place on the sills, which also helps crash protection and torsional rigidity, but more importantly for customers, it means your feet can slide straight across into the footwell.”

The seating position is perfect, the view forward clean, perfectly symmetrical and interrupted chiefly by the ludicrously-numbered rev counter. “However, the central seat and the fact I moved everything as far forward in the car as I could [the driver sits 250mm further forward in the T.50 than the F1] did give us a problem with where to put the mirrors. The only place for them to sit and meet regulations would have been to have them on the tops of the front wheelarches… I shot myself in the foot basically. I didn’t particularly want cameras, but since the F1 [the legislated] mirror size has almost doubled, so the decision to go for cameras was more about aesthetics than aero. It does help though. And lowers wind noise.”

Practicality

“Everyone talks about how good the F1 was with storage around the cabin and the side lockers, but the areas around the cabin didn’t have lids, so if you braked hard all your stuff came flying out, and those lockers, because you had to stoop and lift bags across into them, weren’t that easy to use.

“With the T.50 we have 30 litres of cabin stowage – lockers under both outside seats, plus another pair ahead of each passenger, below the dash – which is more than many SUVs. And you now access the lockers from above. We’ve got two huge butterfly wing doors on a central pivot that lift to reveal the engine and side lockers. We’ll provide fitted luggage. I’m not sure who we’re going to be working with on that yet, although I’ve got a few in mind, but it’ll come with the car. That’s the other thing I don’t like – when you buy car and then the battery charger, the car cover and all the rest are extra.”

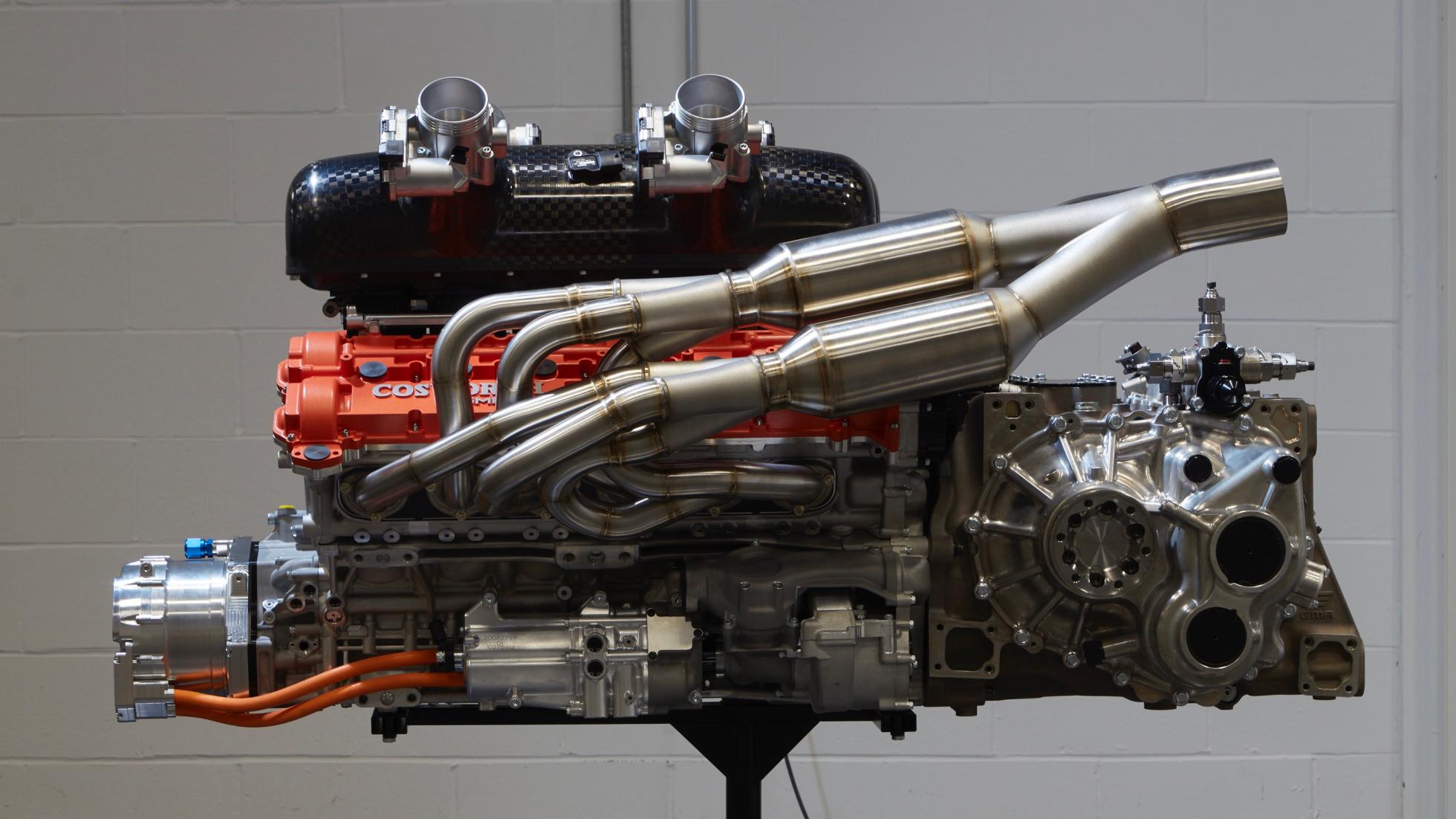

That rev-tastic engine

When Gordon set out the engine parameters with Cosworth there were two main stipulations. Neither of them was a power or torque figure. No, what he asked for was an engine that revved high and revved fast. “I knew the engine would be powerful, but what was much more important to me was what it felt like. It had to be naturally aspirated, and I wanted it to rev higher and faster than two of my other cars. When you blip the throttle in the F1, it gains 10,000rpm per second, and I wanted the T.50 to beat that, plus I wanted it to rev even higher than the LCC [Light Car Company] Rocket.”

That, we should point out, is the highest revving road car ever, powered by a 1.0-litre, five valve, four cylinder Yamaha bike engine capable of hitting 11,500rpm. “So we did all the groundwork with Cosworth and there’s bits I don’t understand – how they play off injection against torque with ignition timing. And my goodness the thermal side of the engine is so clever. But then this little email dropped into my inbox: 12,100rpm and 28,400rpm per second!”

There’s no flywheel – the F1 did without as well – so when you blip the throttle at idle, it’ll hit the redline in 0.3secs. Imagine the sound. These are the claims: the world’s highest revving, fastest responding, most power dense, and lightest naturally aspirated V12.

“It weighs 178kg,” he said, before adding “there’s nothing in common with the [Cosworth-developed Aston Martin] Valkyrie V12, this is really the next generation on.” And the dial that encapsulates all of this for the driver? “Of course the rev counter is mechanical.

“In the 60s you had revs or torque. Couldn’t have both. Now you can. We’ve got two switchable maps – one that limits you to 9,500rpm, 600hp – for supermarket trips. Then click and you’re in high rev mode, but you still have 71 per cent of maximum torque at only 2500rpm. Incredible.”

Fan power

“Not many people seem to know this, but the F1 has two 140mm fans in the diffuser. I wasn’t sure about the tech, so I didn’t push it too hard – I think they delivered about five per cent more downforce, but there wasn’t much in the first place.

“This time round the fan is much more powerful, and can pull air through the engine bay and up from the diffuser. There are six modes, four of them driver selectable, and the main aim isn’t downforce, but stability. For instance, we can stabilise the rear under heavy braking to shave 10 metres from the 240-0km/h stopping distance.

“The fan spins at up to 5,000rpm and moves a lot of air – enough to produce 15kg of thrust. The funkiest mode is Streamline, where we shut the valves to the floor, drop the wing angle to minus ten degrees and pull air from the engine bay. That gives us a 12.5 per cent drag reduction.”

Headlights

“Each headlight pack weighs 2.1kg, including the heat sink and the cooling fan. The heat sink was hidden away underneath, but I thought it looked cool so I asked for it to be visible.”

Style over design?

I tried to catch Gordon out by asking if anything on the car is there for style rather than design. “Absolutely not,” came the reply. But I thought I had something: these little slots cut into the rear light housing. I was wrong. “Actually, those are there to channel cooling air to the rear lights.”

Toolkit and owner's manual

If you’re geeky enough you might be aware that the F1 had a titanium toolkit. It was made by a French company called Facom. “As far as possible I want the T.50 to be British – to use British design and engineering and showcase that – but I also wanted some partnerships to continue. So I called Facom, and the guy was English, and he said ‘would you come to head office to discuss it?’. I said certainly, whereabouts, expecting him to say Paris or something, and he said ‘Slough’. Turns out Black and Decker has bought Facom, so it’s now a British company.”

You may also remember that the F1’s owner’s manual was hand drawn, “and that’s something else we’re going to do again. It’s all about honouring and improving the F1.”

Manual gearbox

“It’ll have the best shift action of any car,” says Gordon, before going into detail about crossgate angles (“only 9 degrees when typical cars are 15”), ratio choice and how they can adjust feel going into and coming out of each slot.

I tell him the finest manual I’ve ever driven belonged to a Honda NSX Type-R. “I copied the NSX for the F1”, he replies, “it was very clever, they sped the cable up so there was never any slack in it.”

The six-speeder is an H-pattern manual from motorsport specialists Xtrac, who have built gearboxes for half the F1 grid. “The lever is mounted on this hybrid carbon and aluminium cantilever so you can see the mechanicsm hanging out the bottom of it. That’s all titanium, and weighs 800g less than the F1.”

Steering

“No-one really cares about steering any more because it’s so difficult. It drives you insane… you go round and round the houses with steering and it never stops. You’re dealing with pneumatic trail, offset to the contact patch, caster angle, kingpin inclination and Ackermann and they all interact. You get one spot on and the others go out of tune.

“But I’m happy I’ve got perfect geometry – and it’s not power-assisted, we just clutch in some assistance below 16km/h to help parking.” That system is patented.

Wheels and tyres

“We don’t need wide tyres because of the weight of car. We reckoned we needed 225s front and 295s at the back for the weight distribution [which is 42:58]. Michelin did their calculations and said we ought to have 235s on front. Another 10mm of tyre and wheel was more weight, but we’ve done it.

“Usually I go for smaller wheels with higher sidewalls. I was upset my Alpine [A110] was a Launch Edition because it was on the bigger wheels, but the tyre technology has improved so much in recent years we’ve actually gone for relatively low profile tyres for the T.50. Obviously that improves steering response, but the bead breaker in the tyre is now so low you can get really good compliance in the sidewall.

“We have to have ABS. The traction and ESP are both switchable.

“The F1 had magnesium wheels, but the technology has changed so much that cast magnesium is now heavier than forged aluminium. Casting is porous, so you need more metal and these days with analysis you can carve out the strength where you need it.

“We had about 20 different designs, but I really like this one. It was the lightest, too.” Hence the most attractive? “Yes.”

Dynamic benchmarking... with Gordon's own Alpine A110

“We’ve actually done some dynamic benchmarking of the T.50 against the Alpine. The only thing I don’t like about it is the steering. When you start to lean on it, it doesn’t weight up very nicely. You jump back in a Lotus Elan and it’s like magic. And the steering wheel rim is too thick. Why? I’ve got long fingers and in the Alpine I can’t get my hands around the wheel.”

On his own F1

Famously, there are elements of the F1 Gordon didn’t like, compromises he had to make. “The spine is 50mm too wide, the headlamps are like glow worms in a jar, the aircon was hopeless, the brakes squeak, the clutch needs adjusting every 5,000 miles, the fuel tank bag needs replacing every five years, loading luggage in the lockers was a pain. This all stuck in my head.”

He owned XP3, the oldest surviving F1, until recently. “I suppose I did about 50,000km in F1s. I sold it because it became untenable to own. When values edged up to £20 million, just the price of insurance….

“Before that, I used to take it out on a Sunday morning. But if you’ve got a £20 million car you think twice about putting someone in it in the rain and showing them a fourth gear slide, so even though I didn’t want it to, it made me think twice.

“I ran this one for 3 years on open pipes. 7,500rpm through a tunnel was fantastic, but it became a bit of a hassle for the MOT, because I’d have to get it changed back each time.”

Murray on the T.50's rivals

“When McLaren announced it was doing a three-seater I was prepared to stop the programme. I got the team together and said ‘I think we’re not going to do this’. I told them they had the legacy and can do it, but then when I saw the Speedtail, I realised it’s not the same at all. We were back on.

“I don’t see us in the same area [as the Valkyrie]. I suspect it’ll be a fantastic car, but I can’t see anyone driving it to the limit. And it’s much heavier.”

Customers

Only 100 cars are being made (half were sold on the basis of a ballpoint sketch), each £2.36 million plus local taxes. “But it’s not £20 million [like an F1], so I point out to customers this is a car that delivers the same experience, but better in every way, and with an 80 per cent discount.”

Customers will spec their cars at Gordon Murray’s Dunsfold premises. “It’ll be very personal, and in the handover centre they’ll be surrounded by some of my own cars… I have 39 cars beneath 900kg.”

Badging

When I’d first looked around the T.50, I cheekily suggested to Gordon that the front and rear badges, clearly enamel, weren’t a lightweight solution, so where else had he let the odd gramme creep in?

“Nowhere,” came the emphatic response, followed by a detailed explanation of the badge design and how it was impossible for enamel to be used more thinly. “It’s all about applying the right technology in the right way. I didn’t want a black carbon plaque or a sticker, I wanted something with more depth, but then to engineer it so it communicates a story of its own. And if you start light everything else gets better.”

STORY Ollie Marriage