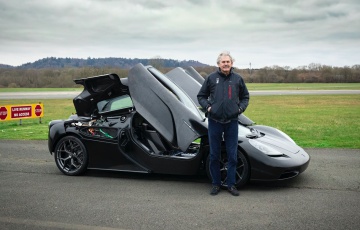

This is it: Gordon Murray's astonishing T.50

Meet the hypercar that does things differently. It doesn’t produce much downforce. It doesn’t care about 0-100km/h times or top speeds.

Power figures are the least impressive thing about the engine. It’s not very big, and it’s not particularly striking to look at.

Everything else about it is absolutely astonishing, though. This is the £2.36m (plus local taxes – for perspective, something like the McLaren Speedtail is £1.75m) GMD T.50. Gordon Murray Design.

(If you haven't seen our video run-through of Gordon Murray's T.50 yet, click HERE)

Yes, the man who gave us the McLaren F1 is now righting that car’s wrongs. Because there were some apparently. “The spine is 50mm too wide, the headlamps are like glow worms in a jar, the air-con was hopeless, the brakes squeak, the clutch needs adjusting every 8,000km, the fuel tank bag replacing every five years, loading luggage in the lockers was a pain. This all stuck in my head”, says Gordon.

You’re aware of how similar the two cars are if you peer in one of the side windows. Those have the same outline, and so too does the solo centre seat.

There are many more commonalities: naturally aspirated V12, 6spd manual gearbox, carbonfibre tub incorporating three seats, lockers in the flanks – but the main one is a laser focus on saving weight.

Because as Gordon points out, “if you start light everything else gets better”.

I start by pointing out the enamel badges. Not the lightest possible solution, so where else had he let the odd gram creep in?

“Nowhere,” came the emphatic response, followed by a detailed explanation of the badge design and how it was impossible for enamel to be used more thinly.

Up close it’s fascinating, but step back and it’s hardly dramatic. The nose, with its large headlights, has curious overtones of the W30 Toyota MR2 (actually a properly lightweight little roadster), and with no bulky intakes or wacky slats and ducts, the flanks are clean and unadorned.

Only the fan in the back makes you do a double take. What would be interesting is to park it alongside a conventional supercar or hypercar, particularly a Bugatti Chiron. Alongside that the Murray would look like a scale model.

The T.50 has roughly the same road footprint as a Mini Clubman – about 1.85 metres wide by 4.35 metres long (it’s about as practical too, with 30 litres of storage around the cabin and sizeable side lockers).

The engine air intake is above the driver’s head and sweeps down the rear deck to form a spine, either side of which butterfly doors open to reveal the low slung engine and storage lockers – loaded from above, not the side as was the case with the F1.

But let’s zoom back in and let Gordon take us through it. To sit in, it’s fabulous. Much easier to clamber aboard than the F1, best done from the left so you don’t catch yourself on the gearlever.

There’s an open flat floor, so you sit backwards on the sill, pivot on your backside and then slide feet into footwell and shuttle in.

It’s light and airy (for passengers as well as driver, although it’s not massive in the flank seats), the windscreen curves around you like a visor and there’s a sense you’ve plugged yourself in: the fit, driving position and sculpted seat are all perfect. And then the symmetry hits you.

Down in the footwell you’ll find a non-symmetrical three-pedal layout. The pedals are gorgeous, skeletal works of art – the lightest ever fitted to a road car, Murray believes, 300 grammes lighter than the F1’s.

The same story is repeated everywhere you look: the titanium gear linkages save 800 grammes.

Each of the full LED headlights weighs just 2.1kg (including the integrated heat sink and cooling fan), the 10-speaker, 700-watt Arcam stereo is half the weight of the Kenwood system in the F1, the titanium chassis plate ahead of the titanium gearlever has been milled out from the back to just 1mm thick, so weighs just 7.8 grammes.

Tenths of a gramme. This is a car we’re dealing with remember. No-one cares about tenths of a gramme.

No-one except Gordon Murray. All up the T.50 weighs 986kg. That’s a wet weight. Dry, it’s about 30kg less than that.

A Chiron is over twice as heavy. Even the F1-inspired Aston Valkyrie is over 100kg more and, we suspect, a lot less comfortable and well kitted out inside.

This hypercar is designed for grand touring, to actually be used and driven. Its USP is excitement and drivability, not downforce or maximum velocity.

Could the engine have been lighter and more powerful if it had fewer cylinders and a pair of turbos? Probably. But that’s not the point.

First you find the right solution, then you work out how to make it lighter. The right solution in this case is a 3.9-litre naturally aspirated V12.

The claims are as follows: the world’s highest revving, fastest responding, most power dense, and lightest naturally aspirated V12. Gordon can’t help adding “there’s nothing in common with the [also Cosworth-developed Aston Martin] Valkyrie V12, this is really the next generation on”.

The fact it develops 663hp and 466Nm are the least interesting facts about it. A savage Ferrari V12 might hit 9,000rpm. This revs to 12,100rpm.

Super-responsive engines such as the F1 and the Lexus LF-A have the ability to gain around 10,000rpm per second if you blip the throttle.

In the T.50 the figure is 28,400rpm. The revs will flare from idle to cutout in 0.3secs. Imagine that. Imagine the noise.

One of the things Gordon is happiest about is that 71 per cent of torque is available at just 2,500rpm.

He still doesn’t know how fast it will accelerate to 100km/h, nor does he care. If he did he wouldn’t have used a manual gearbox.

That weighs 81.5kg alongside the 178kg engine. It’s the work of motorsport specialists Xtrac who have built gearboxes for half the F1 grid.

“It’ll have the best shift action of any car,” says Gordon, before going into detail about crossgate angles (“only 9 degrees when typical cars are 15”), ratio choice and how they can adjust feel going into and coming out of each slot.

Are you getting a picture of how fastidious Murray is? How nothing escapes his laser vision?

What he cares about is delivering the most immersive driving experience possible, not getting around a circuit fastest.

The fan in the back does more than just suck air out of the rear diffuser – even when talking about that aspect, Murray is more interested in the enhanced stability and that he can keep weight on the rear tyres, meaning the T.50 stops 10 metres shorter from 240km/h.

Not once does he mention cornering g. Instead Gordon talks about centres of pressure and limiting drag: “We’ve got six modes, four of them driver selectable, and I think the funkiest is Streamline, where we shut the valves to the floor, drop the wing angle to minus ten degrees and pull air from the engine bay. That gives us a 12.5 per cent drag reduction.”

There are also cameras instead of side mirrors: “Although that was more of an aesthetic decision. Because I wanted to get the driver as far forward as possible, the only place for the mirrors would have been on top of the front wheelarches, which would have looked ridiculous. These reduce the frontal area, lowering drag and wind noise.

T.50 honours and updates the F1 concept. This time there are ABS brakes (a legal necessity), plus traction and stability controls (both fully disable-able).

The steering is once again unassisted, but does clutch in some power assistance below 15km/h to help parking. The Michelin tyres are comparatively narrow (235s at the front, 295s at the back).

Although Murray has traditionally hated low profile tyres, he now says the compliance in the sidewall is such that ride comfort hasn’t suffered. In short the T.50 is a successor to the F1 in the way McLaren’s own Speedtail is not.

“I was prepared to stop the programme”, he says of learning that McLaren was doing its own three-seater, “but when I learned more about it, I realised it was nothing like what we were doing.”

There’s an energy and enthusiasm about Murray, about his diligent quest for engineering perfection.

Where possible he’s used British suppliers, as he wants his car to champion local producers. It’s easy – and wrong – to just see the T.50 as an exercise in light-weighting.

In truth, the way to approach it is to view it as Murray’s take on the ultimate driver’s car.

He’s taking 100 lucky customers along on a very expensive journey, but seeing as over half of them signed up on the basis of a pencil sketch on a piece of paper, we can assume the asking price is no barrier to desirability.

And as Gordon points out, “it’s not £20 million, so I point out to customers this is a car that delivers the same experience [as the F1], but better in every way, and with an 80 per cent discount”.

What do you think the T.50’s legacy will be? “It’s got a good chance of being the last great analogue supercar.”

As epitaphs go as we enter the electric age, that one should stand the test of time.

STORY Ollie Marriage