TG's big 2019 round-up: who's had a bad year?

Aston Martin grabbed headlines by unveiling multiple concept cars at Geneva in March, and pledging in June to take the Valkyrie for the win at Le Mans in 2021. Aston’s vaulting audacity also takes in plans for the Valhalla hypercar, the Vanquish mid-engined supercar, the Lagonda electric EV, plus the still-growing line-up of front-engined cars and the DBX.

We do love ambition. But beneath it all is a continuing slide in profits and investor confidence, and sky-high debt cost. The Valhalla isn’t being snapped up as eagerly as required, nor’s the Vantage. The DBX doesn’t start buttering bread until spring; at the moment, the company stays in the black largely through its hyper-priced historical replicas. Still, as I write, people are going to work at the new factory in Wales.

News has been far tougher for people elsewhere in this country’s car industry. Some 4,500 Jaguar Land Rover workers faced redundancies from February. The company blamed the usual suspects: Europeans buying fewer diesels, Chinese buying fewer of anything… But JLR’s rivals, the same headwinds blowing into their teeth, held up their sales better because they’d got more relevant ranges.

Also, those German rivals aren’t lumbered with the bogey that JLR, like Aston, part-blames for its woe: the Brexit pantomime dragging on another year. “Oh yes we’re leaving on [insert one of several dates here].” “Oh no we’re not.” And “Oh yes we have a deal.” “Oh no we haven’t.” In the vastly complex choreography of international car manufacture, uncertainty is the biggest enemy of all.

Towards the end of the year, things began to perk up for JLR, with cost savings giving better results, and a grand new design centre opening, and something called the Defender. Can’t say the same for Honda, which said it’d shut the Swindon factory in 2022. Before we rush to blame Brexit, note that Honda is also closing a factory in Turkey. It’s a major shift in the company’s ‘we build where we sell’ philosophy.

Nissan, on the other hand, has always explicitly linked its carmaking to politics, and it has reversed an earlier promise to build the next X-Trail in Sunderland. It’ll be Japan now. Finally, Tesla, having looked at Britain for its European factory, settled on Germany. Musk cited the B-word as part of the reason.

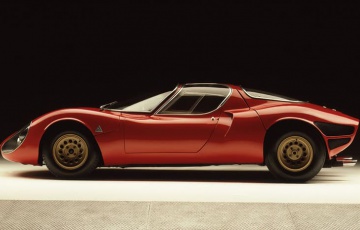

At the exact opposite end of the ambition spectrum from Aston Martin, we find Alfa Romeo. It pared back its model plans. Oh how I tire of writing this. Ever since the days of the 156, successive bosses have talked a glorious rise then presided over withering falls. When the Giulia was unveiled in 2015, Alfa promised us eight cars by the end of last year. Oh. Many were later delayed. Then the plan was rejigged again.

And then again: in September, it put the axe to the Giulietta replacement, big coupe, and also to an eight-cylinder top-end sports car. There will be a version of the Tonale crossover concept, and a smaller one too, but that’s hardly fizzy. And, to stress, Alfa made this latest announcement when it already knew the PSA merger was coming. Couldn’t this vast new enterprise find the money to do the right thing by Alfa?

File, also, under ‘permadelayed’: autonomous cars. Nissan, Mercedes, Renault, BMW and the rest have been predicting them ‘by 2021’ since just ever. Can’t they see 2021 is only a year away? They’re nowhere near ready. Look the engineers in the eye, and they agree their bosses are grandstanding. Tesla is closer – and not just because its self-driving hardware uses much cheaper sensors – but again its predictions have repeatedly slipped. Anyway, this stuff doesn’t look like becoming actually legal to use in the foreseeable, so it’s all a mildly irrelevant multi-billion science experiment.

Big splashes by Aston and others made Geneva the exception among shows. Others stumbled. Frankfurt’s usual bravado was punctured as dozens of manufacturers stayed away, and several of the vast halls were hastily plugged with classic-car exhibits and pretzel stands.

Ferrari pointedly unveiled two cars the eve of opening day, but back at Maranello rather than in Frankfurt. Tokyo the following month was even thinner; people talk of there never being another. A big-show presence costs each manufacturer £3million or so. Many now reckon they can spend it more smartly at local pop-ups and lifestyle events, and targeted digital marketing. At shows, their messages get lost among a noisy throng of rivals.

STORY Paul Horrell